Top ten reads of the year

As 2016 draws to a close, it’s time to take a look back at some of the best books that have appeared here at this blog over the past twelve months. I spent the last year working on a master’s degree, so I didn’t have as much time for pleasure reading as I would have liked, but I ended up reviewing about 90 books for Old Books by Dead Guys. This year’s top crop features a surprising 6-out-of-10 preponderance of science fiction, supplemented by two Georges Simenon thrillers, one nonfiction book, and only one true pre-modernist classic, from Balzac.

The ten titles below are books that I have read (or reread) and reviewed in the past calendar year. Of course, since this is Old Books by Dead Guys, many of these works were published decades ago, but some of them were new to me and may be new to you. Click on the titles below to read the full reviews.

Cousin Bette by Honoré de Balzac (1846)

An aging spinster schemes to get revenge on her more fortunate cousin by teeming up with a beautiful seductress who robs men of their money and morals. Balzac gives us his most cynical view of Parisian society. Just about everyone in the book is despicably greedy, corruption and depravity are commonplace, and love is just another commodity to be traded. It all adds up to an immensely entertaining read, with a few valuable moral lessons taught along the way.

R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) by Karl Capek (1920)

Czech playwright Capek was the first to coin the term “robot.” This science fiction drama is the precursor to all the movies you’ve seen and books you’ve read about robots becoming self-aware, but Capek’s take on the ethics of artificial intelligence feels remarkably fresh almost a century later. The play is also quite lively and entertaining, with an absurdist sense of humor reminiscent of the Dada movement.

The Night at the Crossroads by Georges Simenon (1931)

When Parisian police detective Inspector Maigret is sent to investigate a murder at a country crossroads, the result is something akin to an American gangster film noir. Though usually quite patient and methodical in his investigations, here in the seventh installment of the series Maigret’s a regular action hero, dodging bullets and punching out perps. This may be atypical of the 100 or so adventures in Maigret’s casebook, but it’s one of the more entertaining ones.

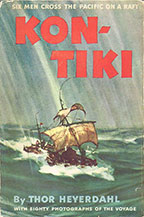

Kon-Tiki by Thor Heyerdahl (1948)

An epic tale of adventure, all the more thrilling because it’s true. In 1947, Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl and a crew of five sailed a balsa wood raft from Peru to Polynesia to support his theory that the Pacific islands were settled by South Americans. His account of this bold archaeological experiment makes for a wild and exciting ride.

Dirty Snow by Georges Simenon (1948)

One of Simenon’s roman durs (hard novels), Dirty Snow is about as dark as noir gets. Taking place in what might be Nazi-occupied France and told from the point of view of a 19-year-old thief and killer, this excellent and disturbing novel calls to mind Camus and Kafka as it transcends the crime thriller genre and ventures into existential philosophy. Possibly one of the best novels of the mid-20th century.

Danny Dunn and the Anti-Gravity Paint by Jay Williams and Raymond Abrashkin (1956)

This one is a throwback to my childhood. Danny Dunn was the star of 15 novels by Williams and Abrashkin, published from 1956 to 1977. Danny is a precocious boy who loves science. Luckily for him, a real live scientist, Professor Bullfinch, is a lodger in his mother’s house. Danny and his friend Joe usually end up commandeering the Professor’s futuristic inventions and getting themselves into a mess of trouble. This first volume, about space travel, is good fun for kids and a great trip down memory lane for those who grew up reading the series, which is now being rereleased as ebooks by Open Road Media.

Omnilingual by H. Beam Piper (1957)

H. Beam Piper’s sci-fi adventures of the 1950s and ’60s are consistently inspired and exciting, and here is one of his best novellas. This story of archaeologists investigating an extinct culture on Mars really captures the thrill of exploration and the joy of scientific discovery. All of Piper’s work is in the public domain, so you can read it for free, or get his complete works in one download for 99 cents with The H. Beam Piper Megapack from Wildside Press.

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood (1985)

The grim future presented by Atwood in this dystopian science fiction novel is scarier than most because it feels like it could actually happen in our lifetime if we’re not careful. The story is narrated by a woman forced into servitude as a surrogate birthing slave, or “Handmaid,” in an ultraconservative society ruled by a religious oligarchy. This is a powerful and moving novel that casts a dark reflection on the state of women’s rights and civil liberties in America today.

I Am Crying All Inside and Other Stories: The Complete Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak, Volume 1 (2015)

Clifford D. Simak, one of the most respected and award-winning science fiction authors of the 20th century, was active from the early 1930s to the mid-1980s. Open Road Media aims to reprint all of his short stories and novellas in a 14-volume series, The Complete Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak, available in ebook and paperback. Simak’s science fiction was truly visionary for its time, and today’s readers will find his stories show almost no signs of age. You might even run across a western or a horror story, because Simak wrote those as well. This series may be my best discovery of 2016.

The Big Front Yard and Other Stories: The Complete Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak, Volume 2 (2015)

And Volume 2 is even better than Volume 1!

And since this is Old Books by Dead Guys, the top ten lists never go out of style. See also my best-of lists for 2013, 2014, and 2015. Keep on reading old books by dead guys in 2017!

Harsh wilderness, tame plot

Conjuror’s House, published in 1903, is a novel by Stewart Edward White, a popular American author of adventure fiction in the early 20th century. The title might lead one to believe the book has supernatural elements, but such an assumption couldn’t be farther from the truth. Conjuror’s House is the unexplained name of a trading post in the remote Canadian wilderness, located where the Moose River flows into Hudson Bay in northern Ontario. Here resides Virginia Albret, a young woman who has lived her entire life in this far-flung corner of the North. Her father, Galen Albret, is the Hudson Bay Company’s head factor of the region. The isolation of the outpost invests his office with an authority far greater than a typical businessman. Albret is the only law in this land, and he rules his little kingdom with a stern hand.

Conjuror’s House, published in 1903, is a novel by Stewart Edward White, a popular American author of adventure fiction in the early 20th century. The title might lead one to believe the book has supernatural elements, but such an assumption couldn’t be farther from the truth. Conjuror’s House is the unexplained name of a trading post in the remote Canadian wilderness, located where the Moose River flows into Hudson Bay in northern Ontario. Here resides Virginia Albret, a young woman who has lived her entire life in this far-flung corner of the North. Her father, Galen Albret, is the Hudson Bay Company’s head factor of the region. The isolation of the outpost invests his office with an authority far greater than a typical businessman. Albret is the only law in this land, and he rules his little kingdom with a stern hand.

A party of French and Indian trappers arrives at the post to conduct their usual business, but this time they’ve brought with them a stranger. Ned Trent is a free trader, unattached to the Hudson Bay Company, who feels the bounty of the wilderness should be free to all. Galen Albret, however, sees Trent as a poacher encroaching on the Company’s territory. The punishment for this offense is a tradition known as “La Longue Traverse.” The offender, allowed only minimal provisions and no weapon, must walk hundreds of miles through the wilderness to reach the nearest sign of civilization. As if starvation and the forces of nature weren’t enough to contend with, the sentenced man will also be hunted down by Indian trackers in the Company’s employ.

This may sound like the premise of a great Jack London novel, but this book really has more in common with the northwestern romances of Canadian author Harold Bindloss. Galen Albret may be one mean and grizzled gangster, but he still maintains the illusion of gentility in his makeshift manor house. His inner circle dresses for dinner every evening and observes the rules of etiquette, thus allowing Virginia to grow up as a proper society lady. Despite her rugged surroundings, she’s still very much a damsel waiting to be plucked from her father’s house by some knight in shining armor. Not surprisingly, she falls in love with Trent.

To its credit, the story is not entirely predictable and does offer some unexpected twists and turns. On the other hand, such departures from convention end up robbing the reader of the very action and confrontation he was hoping for. Like most of Bindloss’s books, this is primarily a Victorian romance novel that just happens to be set in the North, rather than a Jack London-esque adventure where the love story is subservient to the thrills. I really enjoyed White’s writing in the early chapters. His depiction of trading-post life is filled with interesting details, and his descriptions of the wilderness include some beautiful naturalistic passages. He may very well have a great adventure novel in his body of work, but Conjuror’s House isn’t it. Ultimately, the plot let me down as everything fell into place a little too conveniently, resolving conflicts in ways that only squandered the potential for excitement. Conjuror’s House was published the same year as London’s The Call of the Wild. While the latter novel was clearly the harbinger of a new movement in American literature, White’s novel feels like a relic of a bygone era.

If you liked this review, please follow the link below to Amazon.com and give me a “helpful” vote. Thank you.

https://www.amazon.com/review/R2JE9E927VVBOE/ref=cm_cr_rdp_perm

A fascinating tale rather tepidly told

Having recently read Ron Chernow’s excellent biography Washington: A Life, the idea of a book that focused on George Washington’s espionage program really appealed to me. George Washington’s Secret Six, published in 2013, was written by Brian Kilmeade, a Fox News host, and Don Yaeger, a sports journalist. This book came up as a Kindle Daily Deal, and I bought it on impulse without knowing anything about the authors. They definitely wrote the book with the intention of producing a popular bestseller, rather than providing the kind of critical analysis one would get from an academic historian. If that’s the case, however, why is the book so dull? Though I approached the subject matter with my interest already primed, I found Kilmeade and Yaeger’s dry treatment only curbed my enthusiasm.

Having recently read Ron Chernow’s excellent biography Washington: A Life, the idea of a book that focused on George Washington’s espionage program really appealed to me. George Washington’s Secret Six, published in 2013, was written by Brian Kilmeade, a Fox News host, and Don Yaeger, a sports journalist. This book came up as a Kindle Daily Deal, and I bought it on impulse without knowing anything about the authors. They definitely wrote the book with the intention of producing a popular bestseller, rather than providing the kind of critical analysis one would get from an academic historian. If that’s the case, however, why is the book so dull? Though I approached the subject matter with my interest already primed, I found Kilmeade and Yaeger’s dry treatment only curbed my enthusiasm.

The book opens with two chapters that provide an oversimplified synopsis of the Revolutionary War up to 1777. The authors then proceed to tell how Major Benjamin Tallmadge, under the direction of Washington, established a spy ring in Manhattan and Long Island, which were territories under British control. We meet the individual spies as they enter into the fold, learn their back stories and motivations for participating, and hear how they established their network of secret communication. The authors then attempt to illuminate the important role these brave spies played in determining the outcome of the war.

In a brief note at the beginning, the authors warn the reader that the book contains fictional conversations between the personages in the book. The warning hardly seems necessary, however, since so little of such dialogue actually appears in the book. A more common technique of the authors is to tell us what’s going on in the historical characters’ minds, employing a retroactive psychoanalysis that relies heavily on conjectural assumption. When such fictionalized passages do occur, they feel awkward and rather pointless because they do nothing to increase the drama of the narrative. In fact, one thing sorely missing from this book is drama. We hear about the spies transporting letters written in invisible ink, often in code, but Kilmeade and Yaeger never fully convey the import of the letters’ contents or the life-and-death consequences of discovery for those who carry them. Unfortunately the one agent who suffered the most for her service is the one about whom the least is known.

The book climaxes with Benedict Arnold’s traitorous treachery and Major John André’s capture. While Tallmadge played an important part in that tale, the Secret Six don’t seem to feature in it much at all. I will confess that I don’t think I could have even named all the members of the Secret Six until I got to the roll call in the epilogue. The book concentrates mostly on two or three of the six, and there are other minor figures who help out, begging the question why we don’t have a Secret Seven or Eight. I never felt thoroughly engaged in the author’s narrative, and by the end I was just reading to get it done. Contrast this with Chernow, who manages to make Washington’s most mundane actions seem interesting and compelling. The story of Washington and Tallmadge’s espionage ring is inherently fascinating, but that doesn’t come across in this telling of it.

If you liked this review, please follow the link below to Amazon.com and give me a “helpful” vote. Thank you.

https://www.amazon.com/review/R3SNZWVGFO5B7D/ref=cm_cr_rdp_perm

Wisconsin’s ambassador to the galaxy

Clifford D. Simak’s novel Way Station, published in 1963, won the Hugo Award for that year’s best science fiction novel and has been recognized on various “all-time greatest” lists of sci-fi books. Simak, a Science Fiction Writers of America Grand Master, is an author whose work is consistently exceptional and rarely disappoints. Even though this novel was published over 50 years ago, it still reads as a work of brilliantly inspired speculative fiction, and its Cold War-era message remains relevant to the world we live in today.

Clifford D. Simak’s novel Way Station, published in 1963, won the Hugo Award for that year’s best science fiction novel and has been recognized on various “all-time greatest” lists of sci-fi books. Simak, a Science Fiction Writers of America Grand Master, is an author whose work is consistently exceptional and rarely disappoints. Even though this novel was published over 50 years ago, it still reads as a work of brilliantly inspired speculative fiction, and its Cold War-era message remains relevant to the world we live in today.

Way Station tells the story of Enoch Wallace, a veteran of the American Civil War, who is chosen by an extraterrestrial governing body to serve as a sort of galactic innkeeper for interstellar travelers passing through our solar system. The means of travel is a form of teleportation, and Enoch’s rural home is transformed into an arrival, layover, and departure center for wayfarers of myriad alien species and cultures. The interior of Enoch’s house—the way station—exists outside of time, so he does not age when he is inside it. Eventually, a 120-year-old man who looks like he’s in his thirties begins to draw attention. His neighbors become suspicious of their weird, reclusive neighbor. A CIA agent hears rumors of Enoch’s agelessness and puts him under surveillance. These interlopers not only intrude upon Enoch’s privacy; their meddling may also threaten the delicate diplomatic relations between Earth and the rest of the galaxy.

The story is set in rural southwestern Wisconsin, where Simak grew up. He lived his entire life in Wisconsin and Minnesota, and many of his works are set in those states. It’s always refreshing to read a great work of American regional literature that doesn’t take place in one of the nation’s three biggest cities. Occasionally writers will set a work in a generic rural setting, perhaps designating a state such as Kansas or Nebraska for authenticity’s sake. Simak, on the other hand, really establishes a specific sense of place to his setting. You can tell he has had an intimate relationship with the region he describes and the people who dwell there. There is a profound sensitivity to his writing about rural life that’s reminiscent of the work of Willa Cather. Yet the science fiction elements he layers on top of this foundation are as visionary as any other writer of the genre. He judiciously understates the sci-fi elements of the story in order to emphasize the literary over the sensational. A writer like Fritz Leiber would have populated his way station with all manner of far-fetched freakiness, resulting in a weird-for-weird’s-sake view of intergalactic contact (as in The Big Time, for example). Simak, on the other hand, focuses on the humanity in his characters, even those who aren’t human. He aims for more than just thrills and entertainment, instead imbuing his story with an admonishing message of cautious hope for mankind.

Sometimes the story goes off into tangents that seem irrelevant, but eventually Simak brings them back full circle to become integral to the main thrust of the plot. Though quite suspenseful for most of its length, the story lags a little toward the end, and some conflicts are resolved a little too conveniently. Nevertheless, this is a great work of science fiction truly deserving of the accolades it has received. As good as this novel is, however, Simak’s true calling is short stories. If you haven’t done so already, check out Open Road Media’s excellent series The Complete Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak, which is projected to amount to 14 volumes of this master’s work.

If you liked this review, please follow the link below to Amazon.com and give me a “helpful” vote. Thank you.

https://www.amazon.com/review/RVN9GXLLOFGV9/ref=cm_cr_rdp_perm