Top ten reads of the year

As 2016 draws to a close, it’s time to take a look back at some of the best books that have appeared here at this blog over the past twelve months. I spent the last year working on a master’s degree, so I didn’t have as much time for pleasure reading as I would have liked, but I ended up reviewing about 90 books for Old Books by Dead Guys. This year’s top crop features a surprising 6-out-of-10 preponderance of science fiction, supplemented by two Georges Simenon thrillers, one nonfiction book, and only one true pre-modernist classic, from Balzac.

The ten titles below are books that I have read (or reread) and reviewed in the past calendar year. Of course, since this is Old Books by Dead Guys, many of these works were published decades ago, but some of them were new to me and may be new to you. Click on the titles below to read the full reviews.

Cousin Bette by Honoré de Balzac (1846)

An aging spinster schemes to get revenge on her more fortunate cousin by teeming up with a beautiful seductress who robs men of their money and morals. Balzac gives us his most cynical view of Parisian society. Just about everyone in the book is despicably greedy, corruption and depravity are commonplace, and love is just another commodity to be traded. It all adds up to an immensely entertaining read, with a few valuable moral lessons taught along the way.

R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) by Karl Capek (1920)

Czech playwright Capek was the first to coin the term “robot.” This science fiction drama is the precursor to all the movies you’ve seen and books you’ve read about robots becoming self-aware, but Capek’s take on the ethics of artificial intelligence feels remarkably fresh almost a century later. The play is also quite lively and entertaining, with an absurdist sense of humor reminiscent of the Dada movement.

The Night at the Crossroads by Georges Simenon (1931)

When Parisian police detective Inspector Maigret is sent to investigate a murder at a country crossroads, the result is something akin to an American gangster film noir. Though usually quite patient and methodical in his investigations, here in the seventh installment of the series Maigret’s a regular action hero, dodging bullets and punching out perps. This may be atypical of the 100 or so adventures in Maigret’s casebook, but it’s one of the more entertaining ones.

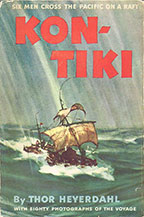

Kon-Tiki by Thor Heyerdahl (1948)

An epic tale of adventure, all the more thrilling because it’s true. In 1947, Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl and a crew of five sailed a balsa wood raft from Peru to Polynesia to support his theory that the Pacific islands were settled by South Americans. His account of this bold archaeological experiment makes for a wild and exciting ride.

Dirty Snow by Georges Simenon (1948)

One of Simenon’s roman durs (hard novels), Dirty Snow is about as dark as noir gets. Taking place in what might be Nazi-occupied France and told from the point of view of a 19-year-old thief and killer, this excellent and disturbing novel calls to mind Camus and Kafka as it transcends the crime thriller genre and ventures into existential philosophy. Possibly one of the best novels of the mid-20th century.

Danny Dunn and the Anti-Gravity Paint by Jay Williams and Raymond Abrashkin (1956)

This one is a throwback to my childhood. Danny Dunn was the star of 15 novels by Williams and Abrashkin, published from 1956 to 1977. Danny is a precocious boy who loves science. Luckily for him, a real live scientist, Professor Bullfinch, is a lodger in his mother’s house. Danny and his friend Joe usually end up commandeering the Professor’s futuristic inventions and getting themselves into a mess of trouble. This first volume, about space travel, is good fun for kids and a great trip down memory lane for those who grew up reading the series, which is now being rereleased as ebooks by Open Road Media.

Omnilingual by H. Beam Piper (1957)

H. Beam Piper’s sci-fi adventures of the 1950s and ’60s are consistently inspired and exciting, and here is one of his best novellas. This story of archaeologists investigating an extinct culture on Mars really captures the thrill of exploration and the joy of scientific discovery. All of Piper’s work is in the public domain, so you can read it for free, or get his complete works in one download for 99 cents with The H. Beam Piper Megapack from Wildside Press.

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood (1985)

The grim future presented by Atwood in this dystopian science fiction novel is scarier than most because it feels like it could actually happen in our lifetime if we’re not careful. The story is narrated by a woman forced into servitude as a surrogate birthing slave, or “Handmaid,” in an ultraconservative society ruled by a religious oligarchy. This is a powerful and moving novel that casts a dark reflection on the state of women’s rights and civil liberties in America today.

I Am Crying All Inside and Other Stories: The Complete Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak, Volume 1 (2015)

Clifford D. Simak, one of the most respected and award-winning science fiction authors of the 20th century, was active from the early 1930s to the mid-1980s. Open Road Media aims to reprint all of his short stories and novellas in a 14-volume series, The Complete Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak, available in ebook and paperback. Simak’s science fiction was truly visionary for its time, and today’s readers will find his stories show almost no signs of age. You might even run across a western or a horror story, because Simak wrote those as well. This series may be my best discovery of 2016.

The Big Front Yard and Other Stories: The Complete Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak, Volume 2 (2015)

And Volume 2 is even better than Volume 1!

And since this is Old Books by Dead Guys, the top ten lists never go out of style. See also my best-of lists for 2013, 2014, and 2015. Keep on reading old books by dead guys in 2017!

Harsh wilderness, tame plot

Conjuror’s House, published in 1903, is a novel by Stewart Edward White, a popular American author of adventure fiction in the early 20th century. The title might lead one to believe the book has supernatural elements, but such an assumption couldn’t be farther from the truth. Conjuror’s House is the unexplained name of a trading post in the remote Canadian wilderness, located where the Moose River flows into Hudson Bay in northern Ontario. Here resides Virginia Albret, a young woman who has lived her entire life in this far-flung corner of the North. Her father, Galen Albret, is the Hudson Bay Company’s head factor of the region. The isolation of the outpost invests his office with an authority far greater than a typical businessman. Albret is the only law in this land, and he rules his little kingdom with a stern hand.

Conjuror’s House, published in 1903, is a novel by Stewart Edward White, a popular American author of adventure fiction in the early 20th century. The title might lead one to believe the book has supernatural elements, but such an assumption couldn’t be farther from the truth. Conjuror’s House is the unexplained name of a trading post in the remote Canadian wilderness, located where the Moose River flows into Hudson Bay in northern Ontario. Here resides Virginia Albret, a young woman who has lived her entire life in this far-flung corner of the North. Her father, Galen Albret, is the Hudson Bay Company’s head factor of the region. The isolation of the outpost invests his office with an authority far greater than a typical businessman. Albret is the only law in this land, and he rules his little kingdom with a stern hand.

A party of French and Indian trappers arrives at the post to conduct their usual business, but this time they’ve brought with them a stranger. Ned Trent is a free trader, unattached to the Hudson Bay Company, who feels the bounty of the wilderness should be free to all. Galen Albret, however, sees Trent as a poacher encroaching on the Company’s territory. The punishment for this offense is a tradition known as “La Longue Traverse.” The offender, allowed only minimal provisions and no weapon, must walk hundreds of miles through the wilderness to reach the nearest sign of civilization. As if starvation and the forces of nature weren’t enough to contend with, the sentenced man will also be hunted down by Indian trackers in the Company’s employ.

This may sound like the premise of a great Jack London novel, but this book really has more in common with the northwestern romances of Canadian author Harold Bindloss. Galen Albret may be one mean and grizzled gangster, but he still maintains the illusion of gentility in his makeshift manor house. His inner circle dresses for dinner every evening and observes the rules of etiquette, thus allowing Virginia to grow up as a proper society lady. Despite her rugged surroundings, she’s still very much a damsel waiting to be plucked from her father’s house by some knight in shining armor. Not surprisingly, she falls in love with Trent.

To its credit, the story is not entirely predictable and does offer some unexpected twists and turns. On the other hand, such departures from convention end up robbing the reader of the very action and confrontation he was hoping for. Like most of Bindloss’s books, this is primarily a Victorian romance novel that just happens to be set in the North, rather than a Jack London-esque adventure where the love story is subservient to the thrills. I really enjoyed White’s writing in the early chapters. His depiction of trading-post life is filled with interesting details, and his descriptions of the wilderness include some beautiful naturalistic passages. He may very well have a great adventure novel in his body of work, but Conjuror’s House isn’t it. Ultimately, the plot let me down as everything fell into place a little too conveniently, resolving conflicts in ways that only squandered the potential for excitement. Conjuror’s House was published the same year as London’s The Call of the Wild. While the latter novel was clearly the harbinger of a new movement in American literature, White’s novel feels like a relic of a bygone era.

If you liked this review, please follow the link below to Amazon.com and give me a “helpful” vote. Thank you.

https://www.amazon.com/review/R2JE9E927VVBOE/ref=cm_cr_rdp_perm

A fascinating tale rather tepidly told

Having recently read Ron Chernow’s excellent biography Washington: A Life, the idea of a book that focused on George Washington’s espionage program really appealed to me. George Washington’s Secret Six, published in 2013, was written by Brian Kilmeade, a Fox News host, and Don Yaeger, a sports journalist. This book came up as a Kindle Daily Deal, and I bought it on impulse without knowing anything about the authors. They definitely wrote the book with the intention of producing a popular bestseller, rather than providing the kind of critical analysis one would get from an academic historian. If that’s the case, however, why is the book so dull? Though I approached the subject matter with my interest already primed, I found Kilmeade and Yaeger’s dry treatment only curbed my enthusiasm.

Having recently read Ron Chernow’s excellent biography Washington: A Life, the idea of a book that focused on George Washington’s espionage program really appealed to me. George Washington’s Secret Six, published in 2013, was written by Brian Kilmeade, a Fox News host, and Don Yaeger, a sports journalist. This book came up as a Kindle Daily Deal, and I bought it on impulse without knowing anything about the authors. They definitely wrote the book with the intention of producing a popular bestseller, rather than providing the kind of critical analysis one would get from an academic historian. If that’s the case, however, why is the book so dull? Though I approached the subject matter with my interest already primed, I found Kilmeade and Yaeger’s dry treatment only curbed my enthusiasm.

The book opens with two chapters that provide an oversimplified synopsis of the Revolutionary War up to 1777. The authors then proceed to tell how Major Benjamin Tallmadge, under the direction of Washington, established a spy ring in Manhattan and Long Island, which were territories under British control. We meet the individual spies as they enter into the fold, learn their back stories and motivations for participating, and hear how they established their network of secret communication. The authors then attempt to illuminate the important role these brave spies played in determining the outcome of the war.

In a brief note at the beginning, the authors warn the reader that the book contains fictional conversations between the personages in the book. The warning hardly seems necessary, however, since so little of such dialogue actually appears in the book. A more common technique of the authors is to tell us what’s going on in the historical characters’ minds, employing a retroactive psychoanalysis that relies heavily on conjectural assumption. When such fictionalized passages do occur, they feel awkward and rather pointless because they do nothing to increase the drama of the narrative. In fact, one thing sorely missing from this book is drama. We hear about the spies transporting letters written in invisible ink, often in code, but Kilmeade and Yaeger never fully convey the import of the letters’ contents or the life-and-death consequences of discovery for those who carry them. Unfortunately the one agent who suffered the most for her service is the one about whom the least is known.

The book climaxes with Benedict Arnold’s traitorous treachery and Major John André’s capture. While Tallmadge played an important part in that tale, the Secret Six don’t seem to feature in it much at all. I will confess that I don’t think I could have even named all the members of the Secret Six until I got to the roll call in the epilogue. The book concentrates mostly on two or three of the six, and there are other minor figures who help out, begging the question why we don’t have a Secret Seven or Eight. I never felt thoroughly engaged in the author’s narrative, and by the end I was just reading to get it done. Contrast this with Chernow, who manages to make Washington’s most mundane actions seem interesting and compelling. The story of Washington and Tallmadge’s espionage ring is inherently fascinating, but that doesn’t come across in this telling of it.

If you liked this review, please follow the link below to Amazon.com and give me a “helpful” vote. Thank you.

https://www.amazon.com/review/R3SNZWVGFO5B7D/ref=cm_cr_rdp_perm

Wisconsin’s ambassador to the galaxy

Clifford D. Simak’s novel Way Station, published in 1963, won the Hugo Award for that year’s best science fiction novel and has been recognized on various “all-time greatest” lists of sci-fi books. Simak, a Science Fiction Writers of America Grand Master, is an author whose work is consistently exceptional and rarely disappoints. Even though this novel was published over 50 years ago, it still reads as a work of brilliantly inspired speculative fiction, and its Cold War-era message remains relevant to the world we live in today.

Clifford D. Simak’s novel Way Station, published in 1963, won the Hugo Award for that year’s best science fiction novel and has been recognized on various “all-time greatest” lists of sci-fi books. Simak, a Science Fiction Writers of America Grand Master, is an author whose work is consistently exceptional and rarely disappoints. Even though this novel was published over 50 years ago, it still reads as a work of brilliantly inspired speculative fiction, and its Cold War-era message remains relevant to the world we live in today.

Way Station tells the story of Enoch Wallace, a veteran of the American Civil War, who is chosen by an extraterrestrial governing body to serve as a sort of galactic innkeeper for interstellar travelers passing through our solar system. The means of travel is a form of teleportation, and Enoch’s rural home is transformed into an arrival, layover, and departure center for wayfarers of myriad alien species and cultures. The interior of Enoch’s house—the way station—exists outside of time, so he does not age when he is inside it. Eventually, a 120-year-old man who looks like he’s in his thirties begins to draw attention. His neighbors become suspicious of their weird, reclusive neighbor. A CIA agent hears rumors of Enoch’s agelessness and puts him under surveillance. These interlopers not only intrude upon Enoch’s privacy; their meddling may also threaten the delicate diplomatic relations between Earth and the rest of the galaxy.

The story is set in rural southwestern Wisconsin, where Simak grew up. He lived his entire life in Wisconsin and Minnesota, and many of his works are set in those states. It’s always refreshing to read a great work of American regional literature that doesn’t take place in one of the nation’s three biggest cities. Occasionally writers will set a work in a generic rural setting, perhaps designating a state such as Kansas or Nebraska for authenticity’s sake. Simak, on the other hand, really establishes a specific sense of place to his setting. You can tell he has had an intimate relationship with the region he describes and the people who dwell there. There is a profound sensitivity to his writing about rural life that’s reminiscent of the work of Willa Cather. Yet the science fiction elements he layers on top of this foundation are as visionary as any other writer of the genre. He judiciously understates the sci-fi elements of the story in order to emphasize the literary over the sensational. A writer like Fritz Leiber would have populated his way station with all manner of far-fetched freakiness, resulting in a weird-for-weird’s-sake view of intergalactic contact (as in The Big Time, for example). Simak, on the other hand, focuses on the humanity in his characters, even those who aren’t human. He aims for more than just thrills and entertainment, instead imbuing his story with an admonishing message of cautious hope for mankind.

Sometimes the story goes off into tangents that seem irrelevant, but eventually Simak brings them back full circle to become integral to the main thrust of the plot. Though quite suspenseful for most of its length, the story lags a little toward the end, and some conflicts are resolved a little too conveniently. Nevertheless, this is a great work of science fiction truly deserving of the accolades it has received. As good as this novel is, however, Simak’s true calling is short stories. If you haven’t done so already, check out Open Road Media’s excellent series The Complete Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak, which is projected to amount to 14 volumes of this master’s work.

If you liked this review, please follow the link below to Amazon.com and give me a “helpful” vote. Thank you.

https://www.amazon.com/review/RVN9GXLLOFGV9/ref=cm_cr_rdp_perm

Little bang in this Buck

Pearl S. Buck won the Nobel Prize for her early novels about China (most notably The Good Earth), which explored the differences between Eastern and Western cultures and the universal humanity that unites the two. After becoming a Nobel Laureate, Buck still had 35 years of career left. She used that time to branch out beyond China into a variety of subjects and settings, becoming a popular historical novelist along the lines of a James Michener. Though she deserves credit for not resting on her laurels, not all of Buck’s experiments were successful. Death in the Castle, published in 1965, proves that amid her prolific output there lies a hacky work or two.

Pearl S. Buck won the Nobel Prize for her early novels about China (most notably The Good Earth), which explored the differences between Eastern and Western cultures and the universal humanity that unites the two. After becoming a Nobel Laureate, Buck still had 35 years of career left. She used that time to branch out beyond China into a variety of subjects and settings, becoming a popular historical novelist along the lines of a James Michener. Though she deserves credit for not resting on her laurels, not all of Buck’s experiments were successful. Death in the Castle, published in 1965, proves that amid her prolific output there lies a hacky work or two.

Starborough Castle, one of the oldest surviving castles in England, is the residence of Sir Richard Sedgley, whose family has lived there for centuries, and his wife Lady Mary. Like feudal lords of old, the Sedgleys preside over the farms of the surrounding countryside, but as modern castle owners they graciously open their home to tourists one day a week. Despite his aristocratic heritage, Sir Richard has fallen on financial hard times. He agrees to meet with a wealthy American, John Blayne, who proposes to turn the castle into an art museum. Due to a miscommunication, the Sedgleys don’t realize until Blayne arrives that what he really intends is to buy the castle and ship it brick by brick to Connecticut. Reluctant to lose his home in this way, Sir Richard refuses Blayne’s offer, but Blayne decides to hang around a while in hopes that he can convince him to change his mind. Blayne’s decision to stay is also influenced by his attraction to the Sedgley’s beautiful servant, Kate Wells, who was born and raised in the castle and is treated as a sort of foster granddaughter.

Like many an old castle, there are rumors of ghosts. The Sedgleys speak of them as a reality, referring to the unseen spirits as they or them (always in italics). Buck never capitalizes on their potential for thrills and chills, however. For most of the novel’s length, nothing much really happens. There are maybe a dozen suspenseful pages out of the 185. It’s all build-up with little payoff, like one of those B-grade horror movies from the ‘70s that takes itself too seriously, where you have to sit through an hour and a half of ominous music before you see any blood. The few shocks the book actually delivers are dulled by being telegraphed far in advance.

Rather than a thriller or a chiller, Death in the Castle reads more like a Harlequin romance novel. I don’t know if I would call Buck a feminist, but she has always had strong female leads in her novels. Here, however, the story is told largely from the perspective of Kate, who comes across as an emotional child, her heart constantly a-flutter over Blayne. Her sole purpose in life seems to be to wait around the castle until a man plucks her from it. She suffers from her servant status, which makes her undesirable to men of quality, yet she’s so beautiful, Buck can’t help but point out, she must have some royal blood in her. While Buck has always backed up her novels with detailed research and intimate knowledge of the countries she’s covered, her depiction of British life here is simplistic and hokey. In a brief author’s note, she says the novel was inspired by a visit she made to a castle in England, and that seems to be the extent of her research.

I’m a fan of Buck’s work, so I kept trying to give her the benefit of the doubt on this one, but the final pages are really cheesy and riddled with clichés. Buck obviously has a good command of the English language, so it’s competently written, but that’s about the best I can say for it.

If you liked this review, please follow the link below to Amazon.com and give me a “helpful” vote. Thank you.

https://www.amazon.com/review/RHHFK9LGTPO3U/ref=cm_cr_rdp_perm

Love, money, and revenge

Cousin Bette, published in 1846, is one of Honoré de Balzac’s lengthiest and most substantial works. In addition to being included in Balzac’s large collection of writings known as the Comédie Humaine, Cousin Bette is paired in a literary diptych with the author’s 1847 novel Cousin Pons, under the heading of Poor Relations. Though both Cousin novels deal with the less fortunate relatives of wealthy families, the stories are unrelated and share no common characters (except perhaps for some cameo appearances in the supporting cast). Of the two, Cousin Bette is a vastly superior book to Cousin Pons. In fact, Cousin Bette may be Balzac’s greatest work, vying for that title with such excellent books as Père Goriot, Lost Illusions, and Eugénie Grandet.

Cousin Bette, published in 1846, is one of Honoré de Balzac’s lengthiest and most substantial works. In addition to being included in Balzac’s large collection of writings known as the Comédie Humaine, Cousin Bette is paired in a literary diptych with the author’s 1847 novel Cousin Pons, under the heading of Poor Relations. Though both Cousin novels deal with the less fortunate relatives of wealthy families, the stories are unrelated and share no common characters (except perhaps for some cameo appearances in the supporting cast). Of the two, Cousin Bette is a vastly superior book to Cousin Pons. In fact, Cousin Bette may be Balzac’s greatest work, vying for that title with such excellent books as Père Goriot, Lost Illusions, and Eugénie Grandet.

The ensemble cast is large and the plot is quite complicated. The web of relationships between the myriad characters isn’t quite as byzantine as The Count of Monte Cristo, but close. Lisbeth “Bette” Fischer has always envied and resented her wealthier, more attractive cousin Adeline. The two grew up together, and Adeline was always treated like a princess while Bette was regarded as little more than a servant. Now in their forties, Bette is a spinster and embroidery entrepreneur while Adeline is a beautiful baroness. Bette is always welcome for dinner in the Hulot house, and she keeps her ill feelings well hidden. However, when a young man that Bette has had her eye on is stolen by Adeline’s lovely daughter Hortense, Bette resolves to have her revenge on the family that has always looked down upon her. Meanwhile Adeline’s husband, the Baron Hulot, has set his sights on a new mistress, Valérie Marneffe, a married woman whose husband is happy to act as her pimp if it brings him profit. Bette befriends Valérie, and together the two scheme to bring the Hulot family to misery and ruin.

For a man who wrote many cynical books, Cousin Bette may be his most cynical. Everyone is out for money, depravity and corruption are commonplace, and love is just another commodity to be traded. Balzac discusses sexuality with surprising openness, particularly when compared to the puritanical and prudish American literature of the same time period. Valérie is a lot like Emile Zola’s strumpet heroine Nana, but a lot smarter. She juggles multiple lovers, pitting them against one another as competitive bidders for her affection, sucking them dry of funds. Zola clearly read Cousin Bette before writing Nana, and the book may in fact have been an important influence on Zola’s development of literary naturalism.

All this vindictive backstabbing may sound depressing, but it’s not. It’s actually a whole lot of fun. As in Wuthering Heights, the reader derives pleasure from this dysfunctional family’s misfortunes. Balzac strikes the perfect balance of lighthearted naughtiness and serious moral melodrama throughout. Amidst all the sin and degradation, there are nonetheless glimmers of righteousness and hope in humanity. Adeline, for example, demonstrates saintly devotion to her husband, despite his selfish waywardness. There are some truly memorable moments of pathos and poignancy interspersed amid all the ribald humor. The book makes some valid points about how money has eroded spiritual dignity and tainted the purity of love and family, yet Balzac never succumbs to preachiness. Despite its length and complexity, Cousin Bette is so enjoyable it feels like a breezy read, at least by 19th century standards. It is the perfectly satisfying product of a master novelist operating at the top of his game.

If you liked this review, please follow the link below to Amazon.com and give me a “helpful” vote. Thank you.

https://www.amazon.com/review/RH0O9FE4I0SFN/ref=cm_cr_rdp_perm

Another chapter, another funeral

Mary Shelley’s novel The Last Man was originally published in 1826. As the title indicates, it is a post-apocalyptic science fiction novel, a category of literature that I usually enjoy. Though technically it does fulfill the requirements of the genre, it doesn’t do so in a satisfying way. Shelly spends so much time leading up to the apocalypse that you barely even get to the post.

Mary Shelley’s novel The Last Man was originally published in 1826. As the title indicates, it is a post-apocalyptic science fiction novel, a category of literature that I usually enjoy. Though technically it does fulfill the requirements of the genre, it doesn’t do so in a satisfying way. Shelly spends so much time leading up to the apocalypse that you barely even get to the post.

The story takes place in the late 20th century. Back when Shelley wrote the book, you couldn’t just tell a story set in the future. You had to come up with some device by which the story could conceivably be read by 19th-century readers. To accomplish this, she opens the book with a silly prologue about how this manuscript was found in a cave in Italy. It was transcribed by an ancient sibyl who prophetically read the future book through psychic means.

The narrator of the story is Lionel Verney. The son of an English nobleman whose father fell from grace with the crown, he has been reduced to herding sheep. For many years he harbors an understandable hatred toward the throne until he meets Adrian, Earl of Windsor, who through brotherly friendship pacifies Verney and wins him over. When England’s monarchical government is dissolved in favor of a republic, an ambitious war hero named Lord Raymond aspires to lead the nation. It’s been said by literary scholars that Shelley based the character of Verney on herself, Adrian on her husband Percy Shelley, and Raymond on their friend Lord Byron. If so, they must have had one strange relationship because Raymond is universally adored as a flawless godhead whose very Christlike downfall causes God to punish the world with cataclysm. At least half of the book is spent on these characters and their love lives before anything interesting happens. After reading through so much overwrought melodrama, this world couldn’t end soon enough for me.

When the apocalypse does finally arrive, it comes with a whimper rather than a bang. The fun part about the post-apocalyptic genre is imagining what the world will be like after almost everyone is gone, but we really don’t get much of that here. It just takes forever for these people to die. For those that remain alive in the devastated world, moments of hope and industry are few and far between. Towards the end, a tedious pattern emerges in which a different character dies in each chapter, and Verney heaps lamentations upon his or her corpse while contemplating the insignificance of man in the face of nature. After the first few eulogies it gets pretty old.

Another annoying aspect of the book is the way Shelly deals with class. She gives some halfhearted lip service to the idea that the end of the world is the great leveler of social status: “We were all equal now.” Yet the same group of aristocrats is still ruling the world until the very end. Even when England forms a republic, the same rich, blue-blooded lords still rule the roost, like father figures to the helpless, childlike plebs. The one character who is designed to represent the commoners ends up branded a coward. Even when the vast majority of the world’s population has perished, people are still working as servants and innkeepers to Adrian and Verney, despite all the surplus property that must have suddenly become available.

I previously had a disappointing experience with Frankenstein, so I should have known better. Bore me once, Mary Shelley, shame on you. Bore me twice, shame on me.

If you liked this review, please follow the link below to Amazon.com and give me a “helpful” vote. Thank you.

https://www.amazon.com/review/R2AHLFHCH7JQDD/ref=cm_cr_rdp_perm

Nae muckle tae gie excited abit

|

| Sir Walter Scott |

This is the fourth book I’ve reviewed from the ten-volume Stories by English Authors series published by Charles Scribner’s Sons in 1896. Each book in the series is titled after the location in which its stories are set—Scotland in this case, of course. The title is misleading, however, in that the series apparently uses the word “English” to mean “British.” The six authors represented in this collection of short fiction are in fact Scottish, not English. Some of Britain’s greatest literature has come from Scotland, but this isn’t it. Despite the presence of luminaries like Sir Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson, this volume doesn’t admirably represent the state of Scottish literature in the late 19th century.

One problem with Scottish tales, if those included here are any indication, is that authors often feel compelled to dress up their stories in uniquely Scottish local color, starting with the requisite Scottish accent, and apparently the thicker the better. Thus, all the dialogue in these six stories has been transcribed into the Scottish brogue, with varying degrees of success. “No” becomes “nae,” “know” becomes “ken,” “much” becomes “muckle,” and so on. This presents two problems. First and foremost, it can be a pain to read, and sometimes you can’t even figure out what’s being said, so the very story that’s being told is obscured. The second and more vexing problem is when the story itself is rather inconsequential. The author’s primary intention in writing the piece is to demonstrate his prowess in transcribing the highland dialect. In such cases, you end up with formulaic, run-of-the-mill stories dressed up in the trappings of picturesque Scottishness. At least a few of the entries here are guilty of this greater sin.

Perhaps only because I approached this book with optimism, its first entry is its best. In “The Courting of T’nowhead’s Bell” by J. M. Barrie, a young weaver courts his sweetheart, but he’s not the only young man in this rural village who aspires to be the girl’s husband. The competition between the two suitors is quite funny, but you have to wade through the thick accent to get at the humor beneath. Another humorous tale, “The Glenmutchkin Railway” by “Professor Aytoun” has the potential to be funny, but it goes on way too long. It’s about two con artists building a pyramid scheme around an imaginary railroad, but it gets bogged down in stock market minutiae.

The two entries by Scott and Stevenson are worth mentioning because of the authors’ illustrious careers, but the stories included here are far from their best work. Both stories touch on the horror genre and might have been truly scary if not for the painstaking decipherment required to read the text. Scott’s “Wandering Willie’s Tale” concerns a tenant farmer who is denied a receipt for payment of his rent, and has to go to hell to get one. In Stevenson’s “Thrawn Janet,” a fearsome preacher takes as his housekeeper a woman accused of dabbling in deviltry. There are a lot of spooky goings-on, but in the end they don’t add up to anything that makes sense.

Rounding out the collection are “A Doctor of the Old School” by Ian Maclaren and “The Heather Lintie” by S. R. Crockett, probably the least interesting works in the book. Scotland deserves better. How about some Arthur Conan Doyle? It seems these six stories were chosen for their diligent efforts to render the charming national accent into text, with less thought given to their literary merit.

Stories in this collection

The Courting of T’nowhead’s Bell by J. M. Barrie

“The Heather Lintie” by S. R. Crockett

A Doctor of the Old School by Ian Maclaren

Wandering Willie’s Tale by Sir Walter Scott

The Glenmutchkin Railway by Professor Aytoun

Thrawn Janet by Robert Louis Stevenson

If you liked this review, please follow the link below to Amazon.com and give me a “helpful” vote. Thank you.

https://www.amazon.com/review/R2ENLI79T28GDL/ref=cm_cr_rdp_perm

Restores pride to a much-maligned label

The term “socialism” has gotten a bad rap in recent years. In current American political discourse, we often hear it bandied about as if it were an insult, even by those who don’t seem to fully understand what the word means. With his 2011 book The “S” Word: A Short History of an American Tradition . . . Socialism, journalist John Nichols hopes to free the term from this newfound pejorative connotation by reminding us that socialism has always held an important place in American political thought.

The term “socialism” has gotten a bad rap in recent years. In current American political discourse, we often hear it bandied about as if it were an insult, even by those who don’t seem to fully understand what the word means. With his 2011 book The “S” Word: A Short History of an American Tradition . . . Socialism, journalist John Nichols hopes to free the term from this newfound pejorative connotation by reminding us that socialism has always held an important place in American political thought.

A few examples of the socialist influence on American politics are obvious—medicare, social security, and the New Deal are often cited as such—but Nichols goes well beyond the expected. He demonstrates, at several points in American history, how confirmed socialists played integral roles in politics and policymaking. He begins by discussing the poetry of Walt Whitman and then turns to the philosophy of Thomas Paine, a radical whose proto-socialistic thought had a profound impact on the formation of the early American republic. The most fascinating chapter discusses Abraham Lincoln, who corresponded with Karl Marx and whose politics were strongly influenced by socialist newspaper editor Horace Greeley.

Nichols also discusses socialism at the state and local levels, focusing particularly on Milwaukee’s long history of socialist politicians and the progressive tradition in Wisconsin. This leads to a chapter on Victor Berger’s battles against the Espionage Act, a draconian law aimed at stifling dissent. Moving into the ‘40s, ‘50s, and ‘60s, Nichols devotes ample coverage to socialist A. Philip Randolph’s impact on the Civil Rights Movement and Michael Harrington’s contributions to the War on Poverty. The book closes with an afterword that sums up the state of socialism in America today.

Although I enjoyed this book and learned much from it, each chapter overstays its welcome a bit. Once Nichols makes his points he has a tendency to hammer them home repeatedly. The textual excerpts he chooses to support his arguments are unnecessarily extensive, often pages in length when a paragraph or two would have sufficed. I would have preferred more chapters on more topics, even if each were treated with less exhaustive depth. By starting with Whitman, Nichols gives the reader the idea that he will be addressing issues of cultural as well as political identity. However, the rest of the book sticks entirely to politics, and Nichols never covers, for example, the influence of socialism on American literature, and vice versa. Political/artistic figures like Upton Sinclair or Jack London are barely mentioned, if at all.

Nevertheless, this really is an inspiring and enlightening book for anyone who has entertained any sympathy toward the political perspective encompassed by the “S” word. In an era when the word “socialism” is hurled as an inflammatory accusation against Bernie Sanders and Barack Obama, our nation needs a book like this. (While he clearly admires Sanders, Nichols has little good to say about Obama, whom he sees, not surprisingly, as having let down the Left.) American discourse ought to be diverse and inclusive enough to allow input from the left end of the political spectrum. That’s what Nichols is aiming for with this book, and America would have a healthier political climate if more people would read it.

If you liked this review, please follow the link below to Amazon.com and give me a “helpful” vote. Thank you.

https://www.amazon.com/review/R2DK112BWK8B1I/ref=cm_cr_rdp_perm

Pitch black noir

Georges Simenon is best known for his Maigret series of detective novels, but he also published what he referred to as “romans durs” (literally, “hard novels”). These are darker psychological novels that, although they still often fall into the genre of crime stories, transcend mere genre fiction and aspire to the realm of literature. That’s not say that Simenon’s usual brand of crime and detective fiction is lacking in literary merit, but if Dirty Snow is any indication, the romans durs are clearly a cut above the rest of his prodigious body of work. Originally published in 1948 under the French title La Neige était sale, Dirty Snow is a remarkable novel. I’ve only read 14 of Simenon’s books so far—a mere drop in the bucket of the 500 he is rumored to have written—but I feel confident in saying that this has got to be one of his best, if not his absolute masterpiece.

Georges Simenon is best known for his Maigret series of detective novels, but he also published what he referred to as “romans durs” (literally, “hard novels”). These are darker psychological novels that, although they still often fall into the genre of crime stories, transcend mere genre fiction and aspire to the realm of literature. That’s not say that Simenon’s usual brand of crime and detective fiction is lacking in literary merit, but if Dirty Snow is any indication, the romans durs are clearly a cut above the rest of his prodigious body of work. Originally published in 1948 under the French title La Neige était sale, Dirty Snow is a remarkable novel. I’ve only read 14 of Simenon’s books so far—a mere drop in the bucket of the 500 he is rumored to have written—but I feel confident in saying that this has got to be one of his best, if not his absolute masterpiece.

Though written in the third person, the story is told from the perspective of Frank Friedmaier, a 19-year-old thug and thief. The book opens with Frank recalling the first time he ever killed a man, for no other reason than just to prove to himself that he could do it. Frank lives in a whorehouse, run by his mother—not off in some red light district, but in a typical working class apartment building. In a city under foreign occupation during wartime, mother and son are prospering, which draws the ire of their neighbors, who are starving and cold. Through his thoughts and actions, Frank clearly demonstrates himself to be a sociopath, with no empathy or sympathy for other human beings, and no apparent concern for himself, for that matter. Given his seemingly utter lack of conscience, morality, and emotion, how does one explain the strange obsession he develops toward his neighbor, an unassuming street car driver named Holst?

Given the author’s nationality and time of publication, I assume this novel was set in Nazi-occupied France. However, I can’t say for sure whether that’s ever explicitly stated in the narrative. Simenon refers to the invading regime simply as the Occupation. This ambiguity gives the novel a timeless, dystopian quality. It could apply to any nation in wartime, in any era. The shocking thing about the book is that the Nazis, or whoever they are, aren’t really even the villains in the story. Frank is the bad guy; in fact, he’s one of the most despicable human beings you’ll ever encounter in literature, yet you can’t help but identify with him and be compelled by his story.

It’s hard to believe this book was written in 1948, considering how dark, psychologically brutal, and nihilistic it is. The American noir of Raymond Chandler or Mickey Spillane seem cartoony by comparison. It even makes Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead, also published in 1948, seem tame. Critics often liken Simenon to Albert Camus, and there’s definitely some validity to that comparison, but Dirty Snow feels more like one of Franz Kafka’s dark visions. Although it’s a far cry from Maigret, at its heart Dirty Snow is still very much a baffling mystery, as the reader struggles to understand the reasons behind certain events and to figure out just what the hell is going on in Frank’s brain. In the end, as in real life, some questions remain unanswered.

Dirty Snow is a profound and gripping book. I hesitate to say I enjoyed it, given how disturbing it is, but it does produce a powerful, indelible emotional effect. It is the epitome of existential noir thrillers and quite possibly one of the best novels of the mid-20th century.

If you liked this review, please follow the link below to Amazon.com and give me a “helpful” vote. Thank you.

https://www.amazon.com/review/R12XSKLL5VXHEC/ref=cm_cr_rdp_perm

Congratulations to Bob Dylan!

Though there has been talk about the possibility for years, I could not have been more surprised to read this morning that American songwriter Bob Dylan has won the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature. The American press loves to whine that the Nobel jury are a bunch of stuffy, ivory-tower America-haters. What a way to prove them wrong! I couldn’t be more pleased that Dylan has finally gotten the literary recognition he deserves.

Though there has been talk about the possibility for years, I could not have been more surprised to read this morning that American songwriter Bob Dylan has won the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature. The American press loves to whine that the Nobel jury are a bunch of stuffy, ivory-tower America-haters. What a way to prove them wrong! I couldn’t be more pleased that Dylan has finally gotten the literary recognition he deserves.

In honor of the annual occasion, it’s once again time to post the cumulative listing of all the novels, stories, plays, poetry, and memoirs written by Nobel Prize-winning authors that have been reviewed at Old Books by Dead Guys. Since last year, several new works have been added, and four new authors have joined the list: George Bernard Shaw, Pär Lagerkvist, and Halldór Laxness, in addition to Dylan, who’s way down at the bottom of this chronological list. I’m currently working on Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, but didn’t finish it in time, so he’ll have to wait until next year. Once again, congrats to Dylan! Click on the links below to read the complete reviews.

Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1903 Nobel) Norway

Henryk Sienkiewicz (1905 Nobel) Poland

Rudyard Kipling (1907 Nobel) United Kingdom

Selma Lagerlöf (1909 Nobel) Sweden

Paul von Heyse (1910 Nobel) Germany

Maurice Maeterlinck (1911 Nobel) Belgium

Gerhart Hauptmann (1912 Nobel) Germany

Knut Hamsun (1920 Nobel) Norway

Anatole France (1921 Nobel) France

Wladyslaw Reymont (1924 Nobel) Poland

George Benard Shaw (1925 Nobel) Ireland

Sinclair Lewis (1930 Nobel) United States of America

Eugene O’Neill (1936 Nobel) United States of America

Pearl S. Buck (1938 Nobel) United States of America (raised in China)

Hermann Hesse (1946 Nobel) Switzerland (born in Germany)

Pär Lagerkvist (1951 Nobel) Sweden

Halldór Laxness (1955 Nobel) Iceland

Bob Dylan (2016 Nobel) United States of America

See you next year!